Intent-based protocols pt1: unfolding UniswapX

In part 1 of our series on intent-based protocols, we break down UniswapX.

tl;dr

- UniswapX enables off-chain counterparty discovery with on-chain settlement

- The protocol uses Dutch orders parameterized with an RFQ system to facilitate competitive pricing for swappers via sources of on and off-chain liquidity

- Improved UX; abstracts gas, internalizes MEV, compliments AMM liquidity & V4’s hooks

- Offers cross-chain swaps, including fast Ethereum to rollup asset movement

What is UniswapX?

UniswapX is a Dutch order based trading protocol for routing and aggregating liquidity, using signed off-chain orders that are executed and settled on-chain. The protocol provides swappers (traders) with gas abstraction, price improvement from internalized MEV, access to both on and off-chain sources of liquidity, and cross-chain swaps.

Swappers sign off-chain orders, which are submitted on-chain by fillers who pay gas on swappers' behalf. The competition amongst fillers is what affords the best prices for swappers. Dutch Orders are parameterized with an RFQ system. The worst price a user receives in the auction will be the best price available over Uni v2-v3 pools.

UniswapX does not specify how fillers source liquidity for swappers orders: liquidity can be sourced from a combination of on-chain liquidity sources like Uniswap, other DEXs, off-chain liquidity, or from other UniswapX orders. Multiple orders can be bundled into the same transaction, which can also execute other actions atomically on-chain.

Cross-chain UniswapX is a powerful primitive that leverages native asset swaps and optimistic challenge games to provide fast bridging that is compatible with any message passing protocol.

Brief History

Uniswap popularized the concept of Automated Market Makers, first popularized by Hanson’s logarithmic market scoring rule (LMSR) for prediction markets, to Ethereum. Automated market makers (AMMs) are agents that pool liquidity and make it available to traders according to an algorithm. AMMs are useful for creating markets on pairs where there is insufficient demand for professional market makers to participate.

In Uniswap, Liquidity providers (LPs) market make by depositing two tokens into a pool contract for a particular token pair and receive a receipt token which entitles them to trading fees which are distributed pro-rata to all in-range liquidity at the time of the swap.

v1

Uniswap v1 introduced an on-chain system of smart contracts on Ethereum, that implement a class of AMM called a Constant Product Market Maker (CPMM).

CPMMs allow for the exchange of tokens without the need for a trusted third-party. One main concern for users of these markets is whether prices on decentralized exchanges accurately follow those on centralized exchanges, which currently have more liquidity.

Uniswap v1 pairs store pooled reserves of two assets, and provide liquidity for those two assets, maintaining the invariant, such that the product of the reserves cannot decrease. All tokens in v1 are paired with ETH/ERC20 pairs.

v2

Uniswap v2 introduced the creation of arbitrary ERC20/ERC20 token pairs. It also provides a price oracle which allows other contracts on Ethereum to estimate the time-weighted average price of a pair. In addition, v2 introduced Flash swaps - which allow traders to receive assets and use them elsewhere before paying for them later in the transaction. A protocol fee was introduced for the first time - it can be turned on by DAO governance in the future. v2 also re-architected the protocol contracts to reduce attack surfaces.

v3

Uniswap v3 introduced several new features including concentrated liquidity. Concentrated liquidity makes AMMs more efficient by allowing LPs to provide liquidity in tick ranges where LPs can simulate any custom AMM curve. Other new features included flexible fee tiers, an improved price oracle, and protocol fee governce (fee switch).

v4

Uniswap v4 offers fully custom pools with the introduction of hooks. This allows pool creation with custom order types, dynamic fees and custom curves.

Uniswap V4 features a shared singleton contract for all pools. This creates a gas efficiency benefit when routing across multiple pools. Another feature is flash accounting for the Singleton contract which simplifies atomic swapping/adding and multi-hop trades. EIP-1153 will make flash accounting more efficient. Finally, Uniswap v4 brings back ETH/ERC20 token pairs.

Motivations

Uniswap has two classes of users, LPs and Swappers. With efficient routing and custom hooks, LPs can be properly compensated for absorbing toxic orderflow. With Dutch orders parameterized by a request for quote (RFQ) system, swappers leverage filler competition to receive the best prices. UniswapX focuses on the latter but forms a natural synthesis with the former which V4 addresses.

Routing Problem

In September 2021 Uniswap introduced the Auto-router which splits trades across multiple pools at once. The Auto-router optimizes routing across Uniswap v2, v3, and soon v4.

As AMMs become more flexible, routing gets harder due to increased liquidity fragmentation. Today Uniswap protocols have 100,000s of tokens, four different versions of the protocol, deployments on multiple chains, and multiple liquidity sources. With Uniswap v4 and hooks the routing problem becomes more complicated.

UniswapX attempts to solve this problem by creating a competitive marketplace for routing across liquidity. That market place can be on-chain or off-chain. The more people that can participate in finding the best routes, the best pools, discovering all of the different liquidity, the better prices swappers can get in the long run.

Internalize MEV

UniswapX internalizes MEV, reducing value lost by returning any surplus generated by an order back to the swappers in the form of price improvement. This takes inspiration from the original MEV capturing AMM (McAMM) design.

Dutch Orders

UniswapX uses an order type, a Dutch order, which closely resembles a Dutch auction. The decaying nature of Dutch orders creates a competitive market among fillers to find the best possible price for swappers as soon as possible while keeping some small profit margin for themselves.

Dutch orders execute at a price that depends on the time of its inclusion in a block. The order starts at a price that is estimated to be better for the swapper than the current estimated market price. The order’s price then decays over time until it hits the worst price the swapper would be willing to accept. Fillers are incentivized to fill an order as soon as it is profitable for them to do so. If they wait too long, they risk losing the order to another filler willing to take a smaller profit.

This is similar in concept to a fee escalator design put forth by EIP -2593, the Agoric papers, and thegostep.

Order Parameters

- Input token

- Output token

- Input (output) amount

- Starting output (input) amount

- Minimum output (input) amount

- Decay function

- Claim deadline

- Authorization for the UniswapX reactor contract

RFQ

The UniswapX Protocol does not enforce a specific decay function. One way of parameterizing the Dutch order starting price is to poll a selection of fillers through an off-chain Request For Quote(RFQ) system.

In order to incentivize this network of fillers to offer their best possible price, UniswapX allows orders to specify a filler that receives the exclusive right to fill the order for a brief duration, after which the Dutch auction begins and any filler is able to execute the order. Any order with price improvement over the RFQ best offer can still compete to win the order.

An RFQ system may benefit from using an accompanying reputation or penalty system to limit abuse of the free option that this exclusivity provides fillers and to ensure that swapper user experience does not suffer.

Architecture

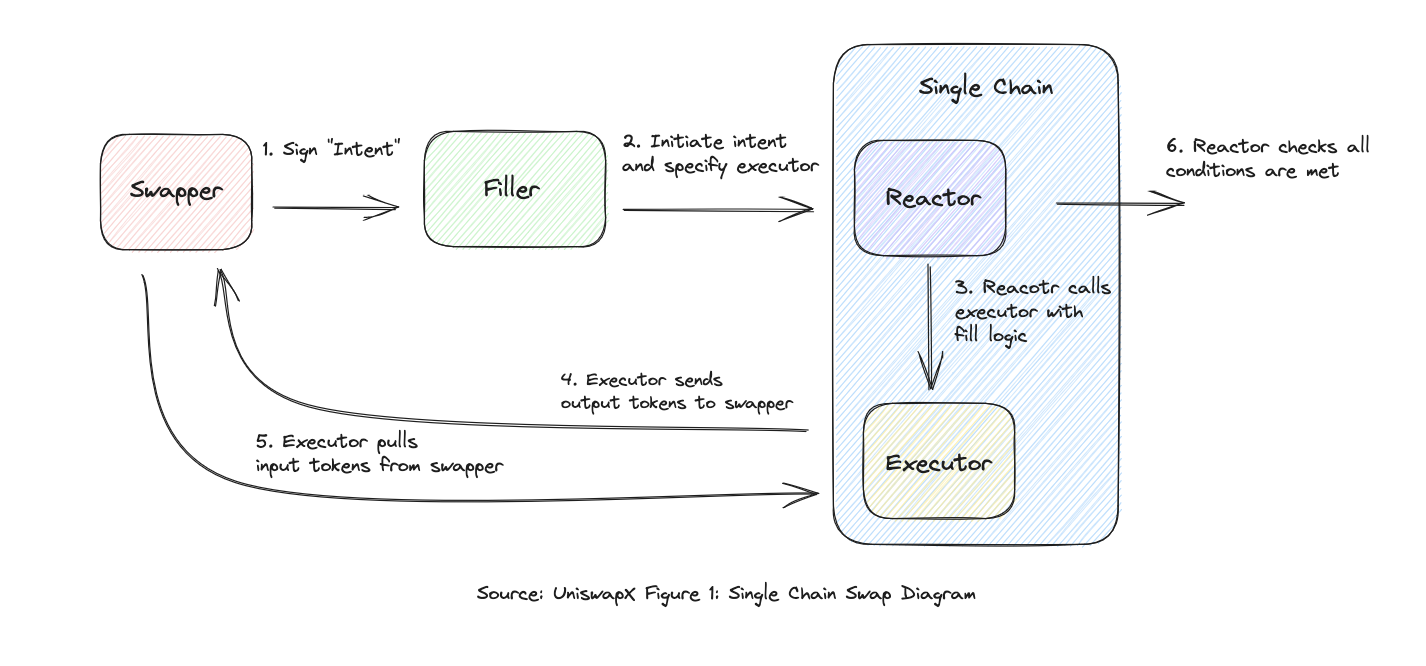

Source: UniswapX White Paper. Note the above diagram deviates slightly from Figure 1.

Agents of the System

- Swapper- users of the application who have intents. Always receive the best possible execution on their orders.

- Fillers - a combination of MEV searchers, market makers, and/or other on-chain agents who pick up user orders and send them to the reactor contract. By submitting swappers’ orders on-chain, fillers pay gas fees on their behalf. These costs are then recouped by factoring gas fees into the execution price.

- Reactors- this contract is responsible for checking that the execution of a trade against the filler’s strategy matches the parameters users expect, and reverting trades that do not.

- Executor - Order fill-contracts which fill UniswapX orders. They specify the filler’s strategy for fulfilling orders and are called by the reactor.

Intent Lifecycle

- User signs an intent.

- Fillers compete for the order in a Dutch Auction.

- The swapper's order starts at price better than the current estimated market price.

- The order decays over time until the order becomes profitable to fill or the worst price the swapper is willing to accept is reached - which could be the best price offered by v2 and v3 AMMs.

- Fillers can also parameterize the Dutch auction starting price with an "off-chain" RFQ system.

- The filler who wins the auction submits the order to the reactor contract "on-chain" which specifies which executor contract to call.

- Executor contract sends output tokens to the swapper.

- Executor contract pulls input tokens from the swapper's address.

- Reactor contract checks all conditions are met.

Example

Note that what follows this is simplified variant of the example found here.

Alice wants to swap 1 ETH for the most USDC she can receive. Alice requests a quote from (potential fillers) Bob and Carlo:

- Bob offers to buy Alice’s ETH for 1,000 USDC

- Carlo offers 999 USDC

- Alice can also swap her 1 ETH directly through Uniswap v3 for 997 USDC

Alice accepts Bob's quote for 1,000 USDC, and signs the order. This order includes a maximum value (set by Bob’s quote of 1,000 USDC) and minimum value of 997 USDC (set by the Uniswap smart order router API). Bob could fill Alice’s order using his own USDC or by routing Alice’s 1 ETH to a variety of on-chain liquidity venues (Uniswap v3, v2, Curve, Sushi). Bob decides to fill Alice’s order using some of his own USDC, and sends Alice 1,000 USDC in exchange for her 1 ETH.

Alternatively, If Bob had decided to fall through on his offer, Alice is not required to submit a new order and signature. Instead, her existing order automatically updates, offering her 1 ETH to any filler who can give her 999 USDC in return. One block has passed and none of the other fillers are willing to fill Alices’s order at 999 USDC. After another Ethereum block (12 seconds) has expired, Alice’s 1 ETH becomes available for 998 USDC. Suddenly, Carlo realizes that he can fill Alice’s 1 ETH sell order for 998 USDC while still collecting a 1 USDC profit by routing Alice’s trade to a combination of Uniswap v3 and Curve v2. Carlo sends Alice 1 ETH to Uniswap v3 and Curve v2 on Alice’s behalf, returning 998 USDC to Alice and keeping the remaining 1 USDC output.

This price improvement over Uniswap v3 is achieved by sourcing liquidity from multiple venues and capturing surplus value from advanced order routing that would otherwise be left for a MEV searcher to capture.

Cross-Chain Orders

Simplified

To initiate a cross-chain order, the swapper signs an off-chain order that includes the same parameters as a single-chain order described above, alongside the following parameters:

- Settlement oracle - a one-way oracle that can attest to events occurring on some destination chain.

- Canonical rollup bridge

- Light client bridge

- Third party bridge

- Fill deadline - time before which the order must be filled on the destination chain

- Filler bond amount and filler bond asset — the bond that the filler must deposit on the origin chain

- Proof deadline — the time before which the filler must prove their fill on the origin chain

Cross Chain Tx Lifecycle

- The filler executes an order by first claiming the swapper’s order and submitting the filler bond to the origin chain reactor contract, and then by transferring assets to the swapper’s address on the destination chain via the destination chain reactor contract.

- The reactor contract records that the order was filled before the fill deadline and relays a message through the settlement oracle back to the reactor contract on the origin chain confirming fulfillment of swapper’s order.

- The swapper’s assets, alongside the bond, are then released to the filler on the origin chain. In the event that the filler does not execute the order before the proof deadline, the swapper receives both their input assets and the filler’s bond from the reactor contract on the origin chain.

Optimistic

Settlement oracles may be slow or expensive. An optimistic cross-chain protocol can alleviate these settlement delay issues, effectively building a fast and cheap bridge on top of any slow bridge. The optimistic protocol includes the same parameters as the simplified protocol, and these additional parameters:

- Challenge bond amount and challenge bond asset - the amount that a challenger must post as a bond on the origin chain.

- Challenge deadline — the deadline before which a challenger can challenge a fill. This must be before the proof deadline.

Optimistic Cross-Chain Tx Lifecycle

In the optimistic case everything is the same as decribed above except, if the filler fills the swapper’s order on the destination chain before the fill deadline, and no one challenges the fill before the end of the challenge period, the filler receives the swapper’s funds, alongside their filler bond, on the origin chain.

Challenge game

- Anyone can challenge the filler after the fill deadline but before the challenge deadline expires

- Challenge is made by using the reactor contract on the origin chain

- If the fill is challenged, the filler must provide a proof before the proof deadline from settlement oracle

- If the filler proves that they filled the order before the proof deadline they receive the challenger’s bond

- If the filler fails to provide a valid proof, the filler’s bond is split between challenger and swapper

- The swapper’s funds are returned to them on the origin chain

Future Considerations

Fees

UniswapX has the same fee switch present in Uniswap V2/V3 which governance has control over. The DAO can vote to turn on a 5 bp fee for each swap of a given token pair. The fee would need to be activiated on each chain that UniswapX is deployed on individually.

Accountability for Fillers

Intents introduce a degree of freedom for fillers to improve efficiency, UX and other conditions of satisfaction. Here we introduce a principal-agent problem (PAP) with fillers.

Today the filler role is permissioned and the actions they can take are constrained. Is there an accountability framework that exists such that fillers can be permissionless which ensures they do not collude to offer users sub-optimal fills that can be tracked by the community?

The Skip team is actively thinking about this problem in the Cosmos ecosystem and recently introduced a reputation dashboard for dydx Validators which monitors order-book discrepencies. While public dashboards for UniswapX exist, it will be important to monitor filler behaviour over time to keep them accountable.

Other work on accountability, operators, and MEV include variants of social slashing like this proposal put forth by Osmosis governance. The slow game is also an example of an accountability mechanism by users to keep operators honest, allowing users to switch away from extractive operators by “force”.

MEV

UniswapX may have a material impact on the MEV supply chaintransaction supply network by reducing the amount of uninformed (retail) orderflow traded against on-chain liquidity. Providing liquidity as an AMM LP may become more difficult to justify as a result of the reduced trading activity on-chain.

In addition, UniswapX fillers have the first look at retail orders and a chance to fill them. AMM LPs receive whatever is left over, including toxic orderflow that professional market makers won't fill. Hooks in V4 can help reduce the amount of LVR exposed by passive LPs by introducing dynamic fees for example.

Perhaps arbitrage opportunities between AMMs on Ethereum decrease as there is less passive liquidity available to be targeted. This reduces the amount of MEV exposed in the system which lessens the opportunity for integrated searcher-builders to win a significant portion of the blocks.

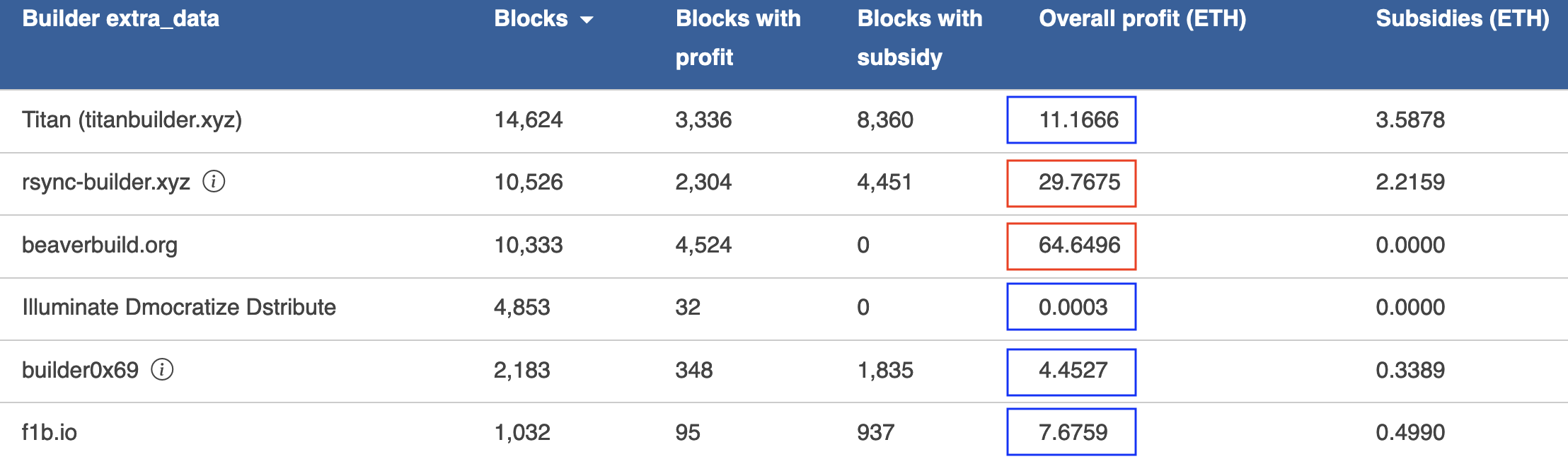

Today, integrated builders win ~45% of blocks. They have an advantage because of their ability to capture CeFi-DeFi arbitrage. When looking at a recent snapshot of builder profitability over the last 7 days, you can see that neutral builders are by-in-large less profitable than integrated builders.

source: relayscan.io

source: relayscan.io

If builders become less incentivized to vertically integrate due to changes in the market structure (UniswapX + Hooks) and instead compete on bundle merging and extra services maybe this achieves a more sustainable equillibrium for the network in the medium-term.

Not everyone agrees with this analysis. It remains to be seen how the transaction supply network evolves going forward. Some think the development of more UniswapX like protocols will lead to more integrated builders, the opposite of the above argument.

Integrations

Hooks

Uniswap v4 introduces a new primitive called Hooks which are externally deployed contracts that execute some custom logic at a specified point in a pool’s execution. Hooks can modify pool parameters, or add new functionality. One naive way to think of Hooks is ABCI++ for AMM pools.

Some features include dynamic fees, TWAMMs, and limit orders. Each new pool when deployed can have its own custom hooks. This will likely spawn tons of experimentation at the cost of fragmenting liquidity. UniswapX can provide routing through v4 pools when complimenting fills with AMM liquidity or finding an optimal path entirely through AMM liquidity.

We may see pools compete to integrate with fillers as a way to have their liquidity and unique hook discovered. There may be a power law distribution of Hooks where a handful dominate most pools with a long-tail of custom hooks.

Extra Builder Services

With the combination of hooks and extra builder services UniswapX could afford features like event driven transactions, pre-confirmations, and order cancelations to name a few.

SUAVE

SUAVE is a decentralized marketplace for MEV mechanisms - SUAVE apps. Developers can deploy MEV applications on SUAVE chain and borrow from SUAVE's credibility and decentralization. This protects users from monopolies because SUAVE provides low switching costs for application users which forces the operators of the mechanisms to remain honest.

UniswapX is one such application that could benefit from SUAVE's credibility and decentralization in the long run. Users would no longer need to trust fillers - TEEs provide integrity and privacy guarantees even in the presence of a malicious operator. With low switching costs between applications, users can hold Fillers accountable while encouraging competition.

Conclusion

The UniswapX protocol improves user experience for Swappers. UniswapX solves the routing problem, internalizes MEV in the form of price improvement, and in the near future introduces trust-minimized cross-chain swaps with an optimistic variant. Open questions remain about privacy, accountability frameworks for fillers, and future integrations.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Yulia and Christopher for draft reviews and feedback. Thanks to Ankit, 0xTaker, Quintus, and Rob Sarrow for discussions around these topics.

All errors, mistakes, and omissions are my own.

Discuss

See you in the forums.