Logic Programming with Differential Equations

We explore differential equations as a surprisingly flexible form of computation. We explore ODEs capable of encoding and solving complex logic problems, unlocking potentially efficient ways to approach tasks like graph coloring and prime factorization.

Introduction

What is the oldest abstract model of universal computation? The most common answer might be the Turing Machine, but those more knowledgeable will know that the Lambda Calculus, General Recursive Functions, and the SK Combinator Calculus all predate Turing machines. But, what if I told you, there has existed a model of universal computation that's hundreds of years old?

We can use ODEs, and, in fact, polynomial ODEs, to perform arbitrary computations. On some level, this is intuitively obvious, as one can model electronic circuitry using ODEs. Some more recent work has connected ODEs to less physical models of computation. For example the paper

- Simulation of Turing machines with analytic discrete ODEs by Manon Blanc and Olivier Bournez

describes how to simulate a Turing machine using an ODE. They start by modeling the Turing machine as a function to . The binary expansion of the first two numbers encodes the left and right sides of the tape, while the last encodes the state of the Turing machine. This is the step function of the machine, and by running it repeatedly, one simulates the action of a Turing machine. This is then turned into an ODE by turning it into a function that takes on the values of the functions whenever the time is an integer value.

There are some interesting methods used in the paper, but I don't find this construction totally satisfying. For one, it doesn't exploit ODEs in any way to accelerate computation, instead restricting things in a very discrete way throughout. Additionally, it relies on encoding things into a Turing machine first; not exactly desirable.

Ideally, we'd like to encode our desired computation more directly. Perhaps the most direct way to encode a desire as a program is through logic/relational programming. Logic programming, at its core, is about writing programs in the form of logical statements. In this paradigm, the emphasis is on specifying what needs to be solved, rather than detailing the steps to solve it. This declarative nature differentiates logic programming from other, more explicit, paradigms. A nice example of this is subtraction. We can define (unary) addition in Prolog recursively, similar to what's done in functional programming. The following defines the relation as add.

add(zero, Y, Y).

add(s(X), Y, s(Z)) :- add(X, Y, Z).

Subtraction can then be defined via addition.

subtract(A, Y, X) :- add(X, Y, A).

This will define the relation as . This elegantly captures the computation of subtraction through its relation to addition. We don't need to concern ourselves with the recursive computation of subtraction; that's implicit in how it relates to addition.

The goal of this post is to explain how we can get something similar using differential equations. We will begin by describing potentials that encode simple logical relations. By following the gradient of these potentials, we will end up at some coordinate that encodes values that make our relation true. We will find that these potentials get too complicated to use in practice for complex logical problems. After that, I will describe one simple method that can be used to combine many simple potentials into more complex ones. This will lead to a simple system of differential equations whose long-term behavior ends up similarly at the bottom of a potential well whose coordinates encode satisfying values. I will focus on the examples of three coloring, addition/subtraction, and, finally, prime factorization to demonstrate the method. At the end, I will briefly go over some related methods to turn logic problems into ODEs.

You may wonder how this post relates to Anoma. I mentioned this method near the end of my survey on constraint satisfaction. This is a general and heavily parallelizable method for incomplete constraint satisfaction, which Anoma is interested in for applications to distributed intent solving. In the survey, I give further pointers to related material, explain formulations of intent solving, and explain how to generalize to approximate solving domains, such as MaxCSP.

Potentials

Before we get into solving, let's look at semantics. We can characterize the semantics of some logic programs fairly easily using continuous functions. The key we will use is that inflection points on functions will often define discrete sets. Specifically, we will encode discrete objects as solutions to equations of the form . Let's start simply by encoding the booleans. Consider the function

one may notice that this function will be 0 if and only if x is either 0 or 1. Further, these points are at a minimum. We may use gradient descent to reach one of these values. This corresponds to the differential equation

We can implement this in JAX like so.

import jax.numpy as jnp

from jax import grad

def V1(x):

return x**2 * (x - 1)**2

def descend(x0, V, dt, n_steps):

x = x0

for _ in range(n_steps):

x -= dt * grad(V)(x)

return x

If we run

descend(V1, 0.55, 0.1, 100).round()

we get 1., indicating that, starting at 0.55 and doing gradient descent, we will eventually end up at 1. We can do something more interesting by looking at functions. As a basic example, we can model an and gate as

def VAnd(v):

x, y, z = v

return (x**2 + y**2 + z**2) * ((x - 1)**2 + y**2 + z**2) * (x**2 + (y - 1)**2 + z**2) * ((x - 1)**2 + (y - 1)**2 + (z - 1)**2)

This overtly encodes the truth table of the function. We may run

descend(VAnd, jnp.array([0.5, 0.5, 0.5]), 0.1, 100).round()

getting [0., 0., 0.], which is, of course, one of the entries of the function. We can run the function on specific arguments;

descend(lambda z: VAnd(jnp.array([0, 1, z])), 0.5, 0.1, 100).round()

getting 0.; the correct output for the function. Significantly, we can also run this backward, like a logic program;

descend(lambda v: VAnd(jnp.array([v[0], v[1], 1])), jnp.array([0.5, 0.5]), 0.1, 100).round()

getting [1., 1.]. This correctly tells us that we can get an output of 1 by issuing 1 and 1 into the arguments.

As our boolean functions grow, such truth tables will grow exponentially, so this will be impractical for larger functions, so we will need to find another way. There is, in fact, a simple solution; given V1 and V2 corresponding to potentials that reach a minimum of 0 at satisfying values, their sum will model the conjunction of the predicates represented by V1 and V2. This gives us a compositional method for building more complex predicates from old ones.

To give an example, we can model xor gates similar to and gates using

def VXor(v):

x, y, z = v

return (x**2 + y**2 + z**2) * ((x - 1)**2 + y**2 + (z - 1)**2) * (x**2 + (y - 1)**2 + (z - 1)**2) * ((x - 1)**2 + (y - 1)**2 + z**2)

we can then combine these into a half-adder as

def VHAddr(v):

i0, i1, s, c = v

return VXor(jnp.array([i0, i1, s])) + VAnd(jnp.array([i0, i1, c]))

and we can use it to do bit addition

descend(lambda v: VHAddr(jnp.array([1, 1, v[0], v[1]])), jnp.array([0.5, 0.5]), 0.1, 100).round()

getting [0., 1.]. So that works, but look at what happens when we try running it backward

descend(lambda v: VHAddr(jnp.array([v[0], v[1], 1, 0])), jnp.array([0.5, 0.5]), 0.1, 100).round()

we get [0., 0.]. Well, that's wrong. There are two correct solutions, and [0, 0] isn't one of them. If we don't round, we instead get [0.46042582, 0.46043378]. Clearly, it's getting stuck at a local minimum. This illustrates a tradeoff we'll see in many potentials. There are potential functions that have only global minima, but, with few exceptions, they will tend to grow exponentially in complexity as their argument number grows. By contrast, there are equivalent (in the sense of having the same minima) potentials that grow linearly in complexity, but they will have local minima that we will have to get past, somehow.

In the next section, I will demo my favorite method for dealing with local minima, but, for the rest of this section, I want to discuss potentials without local minima. Such potentials will be treated as atomic potentials and will define a constraint satisfaction language from which we will build all our larger relations from the atomic ones. Such atomic relations shouldn't have local minima.

How do we improve on the potentials mentioned so far? One issue that may occur to the reader is that they are all higher-order polynomials. Computing them, especially over and over again as we must do for gradient descent, can get expensive. Perhaps worse, these polynomials can give extremely high values if we wander even a little outside the intended domain. These problems can be fixed quite easily. We merely need to replace square with the absolute value function and replace multiplication with taking the minimum value. We may recast the and gate as

def VAndL(v):

x, y, z = v

return min(abs(x) + abs(y) + abs(z), abs(x - 1) + abs(y) + abs(z), abs(x) + abs(y - 1) + abs(z), abs(x - 1) + abs(y - 1) + abs(z - 1))

The derivative becomes what is essentially a big if statement that produces 0, 1, or -1 depending on the region. We can use it the same way as the other implementation

descend(lambda v: VAndL(jnp.array([v[0], v[1], 1])), jnp.array([0.5, 0.5]), 0.1, 100).round()

and it will broadly have the same behavior as far as finding minima goes.

There are other, more clever things we can do. We don't need to have the domain be the entire number line. We can restrict the domain so that the global minima emerge on the edges of the domain. As a basic example, consider

def V2(x):

return -abs(x - 0.5) + 0.5

This will create a spike that peaks at 0.5, and reaches 0 at exactly 0 and 1. If we just do gradient descent, however, we'll go off to the left or right forever. But we can modify our descent function to have a boundary;

def descend_w_boundary(V, x0, dt, n_steps, low, high):

x = x0

for _ in range(n_steps):

x = max(low, min(high, x - dt * grad(V)(x)))

return x

then, when we run the descent, we will hit the boundary and stay there

descend_w_boundary(V2, 0.55, 0.1, 100, 0.0, 1.0)

this will return 1.0.

With this method in mind, modeling boolean relations becomes much easier. Any boolean relation over variables can be modeled with a lookup table with entries. We can describe this as an -dimensional hyperplane cutting through an -dimensional hypercube. Such hyperplanes correspond to essentially unique multi-linear functions. Such functions are called the "Fourier expansion" of the relation they model. If you're interested on why that name is used, you can read about it here;

- Analysis of Boolean Functions by Ryan O'Donnell

I will not go into much detail about the theory here, but we can calculate the expansion from the lookup table via a simple call to a linear solver;

import numpy as np

from scipy.linalg import solve

def find_coefficients(lookup_table):

num_vars = len(lookup_table[0]) - 1

num_equations = len(lookup_table)

num_coefficients = 2 ** num_vars

# Create matrix A for the linear system Ax = b

A = np.zeros((num_equations, num_coefficients))

for i, row in enumerate(lookup_table):

for j in range(num_coefficients):

bits = [int(k) for k in f'{j:0{num_vars}b}']

A[i, j] = np.prod([a if b else 1 for a, b in zip(row[:-1], bits)])

# Create vector b (output values)

b = np.array([row[-1] for row in lookup_table])

# Solve the linear system

coefficients = solve(A, b)

return coefficients

we can run this to find the solution for xor as

lookup_table = [

(0, 0, 0),

(0, 1, 1),

(1, 0, 1),

(1, 1, 0)

]

find_coefficients(lookup_table)

this will return [ 0., 1., 1., -2.], indicating the function

def VXor2(x, y):

return 1 * x + 1 * y - 2 * x * y

Note that this will reproduce the relation verbatim, so doing descent on this will find values where the relation is false. If we want to descend to satisfying values, we merely need to use the potential for the negated relation.

We can use this to calculate nice potentials for any function, though, as one may expect, these tend to increase exponentially in size as the function grows, but this should work well when we have relations with only a few arguments. We can also use this method to characterize some relations that do scale efficiently. If we choose a different encoding, assigning true to 1 and false to -1, then we can find that xor scales very efficiently.

lookup_table = [

(-1, -1, 1),

(-1, 1, -1),

(1, -1, -1),

(1, 1, 1)

]

find_coefficients(lookup_table)

this will return [ 0., 0., 0., 1.].

adding another argument;

lookup_table = [

(-1, -1, -1, -1),

(-1, -1, 1, 1),

(-1, 1, -1, 1),

(-1, 1, 1, -1),

(1, -1, -1, 1),

(1, -1, 1, -1),

(1, 1, -1, -1),

(1, 1, 1, 1)

]

find_coefficients(lookup_table)

we get array([0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 1.]). For xors of arbitrarily many arguments, the Fourier expansion is just the product of all the variables, so long as we use the right encoding.

We could artificially look for other relation families with simple expansions, but I've not had luck finding anything useful other than xors, and material equivalences, which can be defined in terms of xors.

The last I will say about typical boolean relations is that we can model and using min and or using max. These will work with either the false = 0 or false = -1 encodings.

There are lots of other ways to make nice relations. As a commonplace example, we can do linear equations and linear inequalities. In either case, it's fairly easy to calculate a derivative that will push a value toward the plane defining the threshold. For example, consider the equation

We can detect if a value is above or below the threshold and push the value toward it. The normal vector to the plane is simply the coefficients, , so adding this vector to any point will either push it toward or away from the plane. We can accomplish this by using the normalized distance function as a potential.

def VLin(v):

x, y, z = v

return (2 * x - 3 * y + 4 * z) ** 2 / (2**2 + (-3)**2 + 4**2)

min = descend(VLin, jnp.array([0.5, 0.5, 0.5]), 0.1, 100)

print(min)

VLin(min)

this will return

[0.39655172 0.65517241 0.29310345]

Array(3.21945094e-21, dtype=float64)

We can easily generate such functions given a list of coefficients;

def generate_lin_eq_pot(coefficients):

*coeffs, C = coefficients

coeffs_array = jnp.array(coeffs)

def f(v):

return (jnp.dot(coeffs_array, v) + C) ** 2 / jnp.dot(coeffs_array, coeffs_array)

return f

VLin_alt = generate_lin_eq_pot(jnp.array([2, -3, 4, 0]))

These are, of course, continuous rather than discrete. We can make it discrete by adding additional potentials that enforce such discreteness as its own relation.

We can get linear inequalities by only pushing in one direction. If we wanted to satisfy

we can descend if and only if the values are above, but not below, the threshold.

I've focused on finite domains for most of these examples, but it's not hard to come up with some simpler potentials for characterizing infinite discrete sets. For example,

will reach a minimum of at exactly the integers. We can get the natural numbers by restricting the domain.

One may wonder about other infinite, discrete sets, such as trees. I suspect there may be a way to encode them by embedding them according to some analog of a hamming distance. This may require embedding them into a hyperbolic space and then simulating differential equations within said space. I haven't done or seen much work on this topic, so I'll leave it as future research.

Three Coloring

In this section, I'd like to start talking about how to deal with local minima. The problem this section will focus on is the graph three coloring problem. Our goal is to map nodes of a graph onto one of three colors, red, green, or blue, in such a way that no two connected nodes have the same color. We can formulate this as an assertion, for each edge (a, b) in our graph, that color(a) ≠ color(b). We can encode the three colors as the numbers 0, 1, and 2. Using this, we can define the potential function for our inequality as

This potential will be 0 exactly when x and y are assigned to unequal values in . We can, of course, linearize this by using abs and min

and we can restrict the domain so that x and y can only be in the range [0, 2]. However, we may notice a problem. If a variable is red = 0, and its surroundings require it to become blue = 2, then it needs to go past green to get there. This isn't a non-starter; this potential will still work, but this situation adds inefficiency. We can fix this in a few ways, but a simple one is to use the modulus instead. This way, 3 = 0 will now encode red, and it can go in the opposite direction. We can implement our desired potential as

def mod_dist(a, b, mod):

return jnp.abs((a - b + mod / 2) % mod - mod / 2)

def pot(x, y):

tuples = list(product([0, 1, 2], repeat=2))

values = [mod_dist(x, i, 3) + mod_dist(y, j, 3) for i, j in tuples if i != j]

return jnp.min(jnp.array(values))

Now that that's sorted, how do we combine the potentials from all the edges in a graph into something that can be practically solved? In principle, there are many ways to do this, but I'm going to focus on one. Somewhat recently, a new kind of analog computer has been studied under the name "digital memcomputer". Personally, I hate this name, but it's what they call it. Two special cases, used for solving boolean SAT problems, are described in

- Efficient Solution of Boolean Satisfiability Problems with Digital MemComputing by S.R.B. Bearden, Y.R. Pei, M. Di Ventra

- Implementation of digital MemComputing using standard electronic components by Yuan-Hang Zhang, Massimiliano Di Ventra

What I will use is a varient of the differential equations described there. Specifically, given a list of potentials, , I will simulate

for each variable i, and clause m, where is the mth element of the softmax of l, and the Greek letters are hyperparameters that must be tuned. These equations add a short-term memory, , and a long-term memory, , for each clause. The idea is that the short-term memory keeps track of whether the clause is satisfied. It lags, implementing a kind of momentum. The long-term memory will increase so long as the clause remains unsatisfied, and slowly decay otherwise. This gives more force to potentials associated with clauses that are difficult to satisfy. If is near , it represents the clause being satisfied, and the system enters into a mode where the long-term memory has less influence, otherwise, if the clause remains unsatisfied, the long-term memory has the most force.

We can implement this in JAX as

class Hyperparameters:

def __init__(self, alpha, beta, gamma, delta, epsilon, zeta, eta):

self.alpha = alpha

self.beta = beta

self.gamma = gamma

self.delta = delta

self.epsilon = epsilon

self.zeta = zeta

def make_euler_step(V_funcs):

grad_V_funcs = [grad(V_m) for V_m in V_funcs]

@jit

def euler_step(y, dt, var_lim, alpha, beta, gamma, delta, epsilon, zeta):

s = y[:len(V_funcs)]

l = y[len(V_funcs):2*len(V_funcs)]

x = y[2*len(V_funcs):]

l_softmax = softmax(l)

V_vals = jnp.array([V_m(x) for V_m in V_funcs])

ds_dt = beta * (s + epsilon) * (V_vals - gamma)

dl_dt = alpha * (V_vals - delta)

grads_V = jnp.array([grad_V_m(x) for grad_V_m in grad_V_funcs])

update_terms = grads_V * (s[:, None] * l_softmax[:, None] + (1 - s[:, None]) * zeta * l_softmax[:, None])

dx_dt = -update_terms.sum(axis=0)

y_updated = y + jnp.concatenate([ds_dt, dl_dt, dx_dt]) * dt

y_updated = y_updated.at[:len(V_funcs)].set(jnp.clip(y_updated[:len(V_funcs)], 0, 1)) # Short-term memory is in [0, 1]

y_updated = y_updated.at[len(V_funcs):2*len(V_funcs)].set(jnp.clip(y_updated[len(V_funcs):2*len(V_funcs)], 0, jnp.inf)) # Long-term memory is > 0

y_updated = y_updated.at[2*len(V_funcs):].set(jnp.mod(y_updated[2*len(V_funcs):], var_lim)) # Variable values

stop_condition = jnp.all(V_vals < delta)

return y_updated, stop_condition

return euler_step

def euler_integration(y0, num_steps, dt, hyperparams, euler_step_jit, var_lim):

y = y0

stop = False

for _ in range(num_steps):

y, stop = euler_step_jit(y, dt, var_lim, hyperparams.alpha, hyperparams.beta, hyperparams.gamma, hyperparams.delta, hyperparams.epsilon, hyperparams.zeta)

if stop:

break

return y

This mostly implements the differential equations verbatim, but it's worth pointing out a few implementation details. First, note that the step function generates a new function with a jit tag. This makes the function compile after potentials are provided. This allows the function to be optimized and run very fast and in parallel. Additionally, this implementation checks if all the potentials are low enough that all the long-term memories are decreasing or . In such a case, we must have found ourselves in a potential well from which our system won't escape, so we may stop early. Also, note that this assumes we want our variable domain to exist in a modded domain. This may need modification for other applications.

We can generate a list of potentials from a graph automatically with

def generate_V_funcs_from_graph(graph):

return [lambda x, i=i, j=j: pot(x[i], x[j]) for i, j in graph]

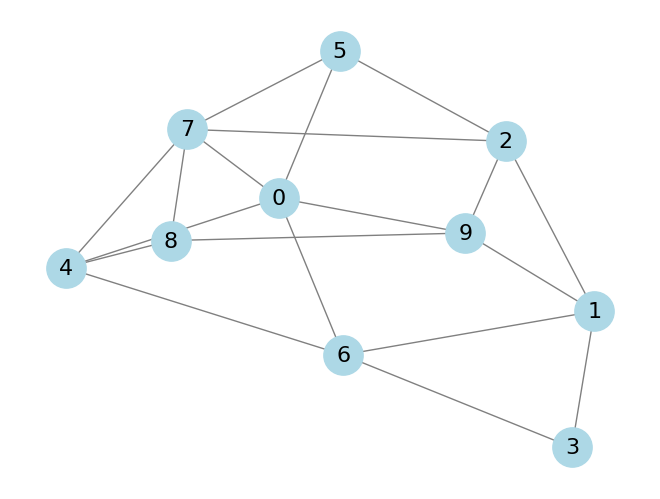

As an example, take the following graph that I randomly generated;

We can prepare this example for simulation with

graph = [(0, 4), (0, 5), (0, 6), (0, 7), (0, 9), (1, 2), (1, 3), (1, 6), (1, 9), (2, 5), (2, 7), (2, 9), (3, 6), (4, 6), (4, 7), (4, 8), (5, 7), (7, 8), (8, 9)]

V_funcs = generate_V_funcs_from_graph(graph)

def initialize_conditions(n_vars, n_clauses, seed=42):

key = random.PRNGKey(seed)

short_term_memory = 0.5 + jnp.zeros(n_clauses)

long_term_memory = jnp.zeros(n_clauses)

variables = 0.01 * (random.uniform(key, (n_vars,)) - 0.5)

return jnp.concatenate([short_term_memory, long_term_memory, variables])

# Simulation parameters

n_vars = 10

n_clauses = len(V_funcs)

hyperparams = Hyperparameters(alpha=5, beta=20, gamma=0.05, delta=0.2, epsilon=0.001, zeta=0.1)

initial_conditions = initialize_conditions(n_vars, n_clauses)

var_lim = 3

euler_step_jit = make_euler_step(V_funcs)

And we can run it with

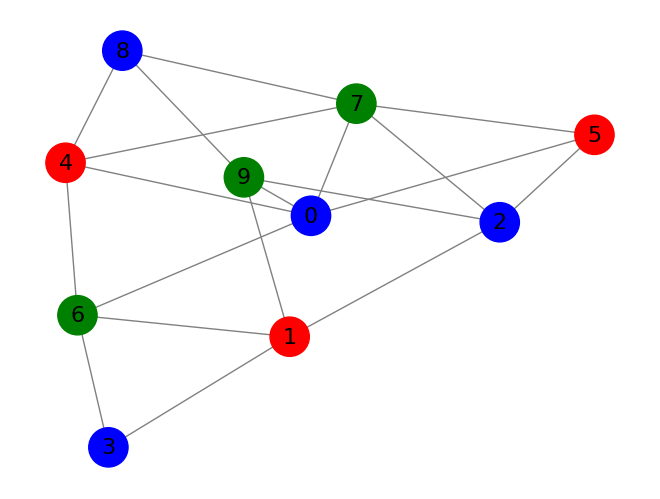

final_state = euler_integration(initial_conditions, 50000000, 0.05, hyperparams, euler_step_jit, var_lim)

We can plot the found coloring with

def display_graph_colored(graph, node_colors):

""" Display the graph with colored nodes. """

G = nx.Graph()

G.add_edges_from(graph)

color_dict = {node: color for node, color in enumerate(node_colors)}

color_map = {0: 'red', 1: 'green', 2: 'blue'}

node_color_list = [color_map[color_dict[node]] if node in color_dict else 'gray' for node in G.nodes]

nx.draw(G, with_labels=True, node_color=node_color_list, edge_color='gray', node_size=800, font_size=16)

plt.show()

display_graph_colored(graph, (final_state[2*n_clauses:].round() % 3).astype(int).tolist())

This method works surprisingly well, but there aren't many guarantees. On many problems, simulation time can vary a lot based on starting conditions, and the simulation is very sensitive to the hyperparameters. It's also somewhat sensitive to numerical precision errors. Making the time step too large will often lead to getting stuck. If you've ever programmed neural networks by hand, messing with this method is quite similar. Often, nothing will work, and it's due to a minor calculation error somewhere that's hard to debug. But, when it does work, it feels a bit magical. It can often rapidly solve problems that seem far too difficult for such a simple method to work on.

Addition and Subtraction

As a second major example, let's try implementing general addition.

I'm going to implement addition between bit-encoded numbers. Originally, rather than going through a boolean circuit, I wanted to implement addition with linear equality. Assuming we have two 8-bit numbers, a and b, we can calculate the 9-bit number by finding boolean values satisfying the linear equality

We can use our previous potential for linear equalities to implement this. To guarantee our variables are actually boolean values, we can, for each variable, add an additional potential with minima at 0 and 1. While this is implementable, it, unfortunately, doesn't work. The issue comes from the linear inequality being too easy to approximately satisfy when it has many involved variables. We would have to tune the hyperparameters to make this harder (specifically by lowering the gamma and delta values), but this interferes with the other constraints, leading to an inability to make progress. I do believe there's some way to make this approach work, but I couldn't for this post, so I'll stick to a more conventional circuit description.

Rather than using logic gates, I will use adder components which should make things simpler. We can generate a multilinear potential function from a lookup table through a modification of the previous coefficient-finding function

def find_multilinear_function(lookup_table):

num_vars = len(lookup_table[0]) - 1

num_equations = len(lookup_table)

num_coefficients = 2 ** num_vars

# Create matrix A for the linear system Ax = b

A = np.zeros((num_equations, num_coefficients))

for i, row in enumerate(lookup_table):

for j in range(num_coefficients):

bits = [int(k) for k in f'{j:0{num_vars}b}']

A[i, j] = np.prod([a if b else 1 for a, b in zip(row[:-1], bits)])

# Create vector b (output values)

b = np.array([row[-1] for row in lookup_table])

coefficients = solve(A, b)

# Define the multilinear function using the coefficients

def multilinear_function(v):

combinations = np.array([[x if b else 1 for x, b in zip(v, [int(bit) for bit in f'{i:0{num_vars}b}'])] for i in range(num_coefficients)])

products = np.prod(combinations, axis=1)

return np.sum(coefficients * products)

return multilinear_function

we can generate lookup tables for full and half adders using

def generate_half_adder_lookup_table():

lookup_table = []

for input1 in [0, 1]:

for input2 in [0, 1]:

sum = (input1 + input2) % 2

carry = (input1 + input2) // 2

for sum_out in [0, 1]:

for carry_out in [0, 1]:

output_correct = (sum_out == sum and carry_out == carry)

lookup_table.append((input1, input2, sum_out, carry_out, 1 - int(output_correct)))

return lookup_table

half_adder_V = find_multilinear_function(generate_half_adder_lookup_table())

def generate_full_adder_lookup_table():

lookup_table = []

for input1 in [0, 1]:

for input2 in [0, 1]:

for carry_in in [0, 1]:

sum = (input1 + input2 + carry_in) % 2

carry = (input1 + input2 + carry_in) // 2

for sum_out in [0, 1]:

for carry_out in [0, 1]:

output_correct = (sum_out == sum and carry_out == carry)

lookup_table.append((input1, input2, carry_in, sum_out, carry_out, 1 - int(output_correct)))

return lookup_table

full_adder_V = find_multilinear_function(generate_full_adder_lookup_table())

Note that these potentials will be 0 when the relation defining the adder is satisfied. The argument order will be the first two input bits, the carry input bit (for the full adder), the sum output bit, and the carry output bit.

Given a fixed bitlength, we can fairly easily tie these into a string of potentials to represent addition.

def generate_addition_potentials(ln):

potentials = []

# Function to create a potential function for a specific bit position

def create_potential(func, idx, ln):

def potential(v):

# Extract relevant bits for the potential function

input1 = v[idx]

input2 = v[ln + idx]

carry_in = v[2 * ln + idx - 1] if idx > 0 else 0 # No carry_in for the first bit

sum_out = v[3 * ln + idx]

carry_out = v[2 * ln + idx]

# Apply the correct potential function

if func == "half_adder":

return half_adder_V(jnp.array([input1, input2, sum_out, carry_out]))

elif func == "full_adder":

return full_adder_V(jnp.array([input1, input2, carry_in, sum_out, carry_out]))

else:

raise ValueError("Invalid function type")

return potential

potentials.append(create_potential("half_adder", 0, ln))

for i in range(1, ln):

potentials.append(create_potential("full_adder", i, ln))

return potentials

In this, each potential accepts a bit-vector whose first ln bits are the first ln-bit input number, the next ln bits are the second number, the third ln bits are the carry bits, and the last ln bits are the first ln bits of the output number. We can then set up the simulation similar to before with

def initialize_conditions(n_vars, n_clauses, seed=42):

key = random.PRNGKey(seed)

short_term_memory = 0.5 + jnp.zeros(n_clauses)

long_term_memory = jnp.zeros(n_clauses)

variables = random.uniform(key, (n_vars,))

return jnp.concatenate([short_term_memory, long_term_memory, variables])

ln = 8

V_funcs = generate_addition_potentials(ln)

# Simulation parameters

n_vars = 4 * ln

n_clauses = len(V_funcs)

hyperparams = Hyperparameters(alpha=5, beta=20, gamma=0.05, delta=0.2, epsilon=0.001, zeta=0.1)

initial_conditions = initialize_conditions(n_vars, n_clauses)

euler_step_jit = make_euler_step(V_funcs)

final_state = euler_integration(initial_conditions, 1000, 0.1, hyperparams, euler_step_jit)

For this example, I replaced this line from `euler_step`

y_updated = y_updated.at[2*len(V_funcs):].set(jnp.mod(y_updated[2*len(V_funcs):], var_lim))

with

y_updated = y_updated.at[2*len(V_funcs):].set(jnp.clip(y_updated[2*len(V_funcs):], 0, 1))

getting rid of var_lim in the process. We can see what numbers it generated with

cond = final_state[2*n_clauses:].round()

print(cond[:ln].astype(int))

print(cond[ln:2*ln].astype(int))

print(cond[(3*ln)-1:].astype(int))

and it returns

[0 1 1 1 1 1 0 0]

[1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0]

[0 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 1]

The first two of these numbers are little-endian bit representations. To get the regular bit representation, we need to reverse the bits, and in doing so we find the first two numbers are 62 and 117. That last number contains the final carry bit as its first bit, and the remaining bits are the first 8 bits of the output in little-endian format. By rotating left by 1 and then reversing the bits, we get the ordinary bit representation of the output. By doing this, we find that the output is 179, which is, indeed, the sum of 62 and 117.

We can modify our simulation to fix some of the inputs;

ln = 8

V_funcs = generate_addition_potentials(ln)

num1 = [1,1,0,1,1,0,0,1] # 155

num2 = [1,0,0,1,0,1,1,0] # 105

V_funcs = [lambda v, V_m=V_m: V_m(jnp.concatenate([jnp.array(num1), jnp.array(num2), v])) for V_m in V_funcs]

# Simulation parameters

n_vars = 2 * ln

[...]

After running this simulation, we can extract the output as

print(final_state[2*n_clauses+ln-1:].round().astype(int))

which returns [1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0]. Again, rotating left and reversing the bits should get us the output sum, which is 260. That is, indeed, the sum of 155 and 105.

And now, the final demo, let's run addition backward. We can implement subtraction by fixing one of the inputs and the output.

ln = 8

V_funcs = generate_addition_potentials(ln)

num1 = [1,1,0,1,1,0,0,1] # 155

num2 = [1,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0] # 260 (rotated right by 1)

V_funcs = [lambda v, V_m=V_m: V_m(jnp.concatenate([jnp.array(num1), v, jnp.array(num2)])) for V_m in V_funcs]

# Simulation parameters

n_vars = 2 * ln - 1

[...]

After the simulation, we can extract the missing input as the bits after the memories and before the carry bits.

print(final_state[2*n_clauses:2*n_clauses+ln].round().astype(int))

this gets us [1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0], which is the little-endian representation of 105, just as expected.

Prime factorization

I want to try something more impressive. I want to do prime factorization with this technique. I'm going to implement a simple multiplication circuit where the adders are a single potential. All the layers of the circuit contain one of the input numbers multiplied by a bit. We can incorporate this into the adder potentials. For example;

def generate_half_adder_2_coef_lookup_table():

lookup_table = []

for coef1 in [0, 1]:

for coef2 in [0, 1]:

for input1 in [0, 1]:

for input2 in [0, 1]:

sum = (coef1 * input1 + coef2 * input2) % 2

carry = (coef1 * input1 + coef2 * input2) // 2

for sum_out in [0, 1]:

for carry_out in [0, 1]:

output_correct = (sum_out == sum and carry_out == carry)

lookup_table.append((coef1, input1, coef2, input2, sum_out, carry_out, 1 - int(output_correct)))

return lookup_table

half_adder_2_coef_V = find_multilinear_function(generate_half_adder_2_coef_lookup_table())

will generate the potential for a half adder where the two added bits are multiplied by two other bits; the coefficients before being added. Similarly, there are three other variants for full adders, including ones where only one of the numbers has a multiplied coefficient.

The least significant output bit doesn't come from an adder, it comes from an and gate being applied to the least bits of the two inputs, so we also need

def generate_and_lookup_table():

lookup_table = []

for input1 in [0, 1]:

for input2 in [0, 1]:

out = int(input1 & input2)

for and_out in [0, 1]:

output_correct = (and_out == out)

lookup_table.append((input1, input2, and_out, 1 - int(output_correct)))

return lookup_table

and_V = find_multilinear_function(generate_and_lookup_table())

with all these, creating the multiplication circuit is quite delicate, but it's not hard to derive it just by looking at the process of using long multiplication to multiply two binary numbers;

def generate_multiplication_potentials(ln):

potentials = []

# Each potential takes a vector with the following anatomy

# - The first ln bits are the bits of the first input

# - The second ln bits are the bits of the second input.

# - The last bit is the first bit of the output

# - All the remaining entries are the bits of carries and inbetween sums.

# There should be ln-1 carry-sum pairs, with each having 2 * ln bits, ln for the carries and ln for the sums.

end = 2 * (ln ** 2)

a_start = 0

b_start = ln

# First digit is `and` of first digits of a and b

potentials.append(lambda v: and_V(jnp.array([v[a_start], v[b_start], v[end]])))

# First layer of addition.

# Assume the number's were multiplying are a = [a0, a1, a2, a3] and b = [b0, b1, b2, b3], where the array are the little-endian bits

# first layer of addition is (a0 * [b1, b2. b3]) + (a1 * [b0, b1, b2, b3]), getting the sum [s00, s01, s02, s03, c03]

# where the s's are stored in the sum sub-vector and c13 is the last bit of the carries

carry0_start = b_start + ln

sum0_start = carry0_start + ln

# First addition is half-added b1 and b0, since there is no carry input. Output here is c00 and s00

potentials.append(lambda v: half_adder_2_coef_V(jnp.array([v[a_start], v[b_start+1], v[a_start+1], v[b_start], v[sum0_start], v[carry0_start]])))

for i in range(1, ln - 1):

# Middle additions use a full adder.

potentials.append(lambda v, i=i: full_adder_2_coef_V(jnp.array([v[a_start], v[b_start+i+1], v[a_start+1], v[b_start+i], v[carry0_start+i-1], v[sum0_start+i], v[carry0_start+i]])))

# since the first layer of addition has fewer bits in the first number, the last addition is just between the penultimate carry and b3.

# This allows us to use a half adder, treating the carry input as a regular input.

potentials.append(lambda v: half_adder_1_coef_V(jnp.array([v[a_start+1], v[b_start+ln-1], v[carry0_start+ln-2], v[sum0_start+ln-1], v[carry0_start+ln-1]])))

# Remaining addition layers

for i in range(1, ln - 1):

last_carry_start = carry0_start + (i-1) * 2 * ln

last_sum_start = last_carry_start + ln

carry_start = last_sum_start + ln

sum_start = carry_start + ln

# We start at aidx = 2 since we already used indexes 0 and 1 at the first addition layer

aidx = a_start + i + 1

# subsequent layers of addition is (a(i+1) * [b0, b1, b2. b3]) + [si1, si2, si3, ci3], getting the sum [s(i+1)0, s(i+1)1, s(i+1)2, s(i+1)3, c(i+1)3]

# The first si0 is dropped as it will be part of the final output.

# The first addition at each layer is a half-adder as we have no carry input

potentials.append(lambda v, aidx=aidx, sum_start=sum_start, carry_start=carry_start, last_sum_start=last_sum_start:

half_adder_1_coef_V(jnp.array([v[aidx], v[b_start], v[last_sum_start+1], v[sum_start], v[carry_start]])))

for j in range(1, ln-1):

bidx = b_start + j

caridx = carry_start + j

lstsumidx = last_sum_start+j+1

sumidx = sum_start + j

# Middle additions are full adders with carry inputs

potentials.append(lambda v, aidx=aidx, bidx=bidx, lstsumidx=lstsumidx, sumidx=sumidx, caridx=caridx:

full_adder_1_coef_V(jnp.array([v[aidx], v[bidx], v[lstsumidx], v[caridx - 1], v[sumidx], v[caridx]])))

# Final addition of each layer must be modified to get the last carry bit rather than a sum bit

potentials.append(lambda v, aidx=aidx, last_carry_start=last_carry_start, carry_start=carry_start, sum_start=sum_start:

full_adder_1_coef_V(jnp.array([v[aidx], v[b_start + ln - 1], v[last_carry_start + ln - 1], v[carry_start + ln - 2], v[sum_start + ln - 1], v[carry_start + ln - 1]])))

return potentials

unfortunately, despite all the work I put into this, it doesn't work too well. I'll discuss why this might be in the next section, but I'll demo what it can do. We can set up the multiplication of three-bit numbers via

ln = 3

V_funcs = generate_multiplication_potentials(ln)

num1 = jnp.array([1,1,0]) # 3

num2 = jnp.array([1,0,1]) # 5

V_funcs = [lambda v, V_m=V_m: V_m(jnp.concatenate([jnp.array(num1), jnp.array(num2), v])) for V_m in V_funcs]

n_vars = 2 * (ln ** 2) + 1 - 2 * ln

[...]

We can then simulate the circuit and extract the output bits, which are distributed across the state vector

final_state = euler_integration(initial_conditions, 100000, 0.1, hyperparams, euler_step_jit)

xs = final_state[2*n_clauses:]

print(jnp.concatenate([

jnp.array(xs[2*(ln**2)-2*ln:]),

jnp.array(xs[ln::2*ln]),

jnp.array(xs[2*(ln**2)-3*ln+1:2*(ln**2)-2*ln]),

jnp.array(xs[2*(ln**2)-3*ln-1:2*(ln**2)-3*ln])

]).round())

this returns [1. 1. 1. 1. 0. 0.], the little-endian representation of 15, which is the correct value. However, trying to multiply other numbers, particularly those with a lot of carries, will usually get stuck. If I manually set the correct answer, it will quickly settle into the global minima, so the issue is that it's not able to escape the local minima. We can run this backward by manually setting the output bits.

ln = 3

V_funcs = generate_multiplication_potentials(ln)

out = jnp.array([1,1,1,1,0,0]) # 15

def make_out(o, x):

out = jnp.array([99.0] * (2 * (ln ** 2) + 1))

out = out.at[:2*ln].set(x[:2*ln])

xs = x[2*ln:]

for i in range(ln):

out = out.at[2*ln+i:2*(ln**2):2*ln].set(xs[i::2*ln-1])

for i in range(ln-1):

out = out.at[2*ln+i+ln+1:2*(ln**2)-ln:2*ln].set(xs[i+ln::2*ln-1])

out = out.at[2 * (ln ** 2)].set(o[0])

out = out.at[2*ln+ln::2*ln].set(o[1:ln])

out = out.at[2*(ln**2)-ln+1:2*(ln**2)].set(o[ln:2*ln-1])

out = out.at[2 * (ln ** 2)-1-ln].set(o[2*ln-1])

return out

V_funcs = [lambda v, V_m=V_m: V_m(make_out(out, v)) for V_m in V_funcs]

n_vars = 2 * (ln ** 2) + 1 - 2 * ln

[...]

And simulating successfully factors

final_state = euler_integration(initial_conditions, 10000, 0.1, hyperparams, euler_step_jit)

xs = final_state[2*n_clauses:]

print(xs[:ln].round())

print(xs[ln:2*ln].round())

this prints [1. 1. 0.] and [1. 0. 1.], the correct prime factors of our input. But, again, this is quite sensitive to inputs and initial conditions. One can more reliably get correct outputs by simulating the system for a few thousand steps across a bunch of different random seeds, but I don't find this too compelling, as one could simply guess the correct answer with comparable effort.

Increasing the bit count makes things much less reliable. There's also the additional problem of compile time. The first time I tried running this I, perhaps arrogantly, tried multiplying two 8-bit numbers. I never even got to the point of running that since it took more than 30 minutes to compile, and I just killed the process after all that time. 4 bits can be done, but I had a hard time finding examples that work, so I stuck to the three-bit example. It's a bit disappointing, but prime factorization is a hard problem, and this is a very generic method, so I was probably expecting too much.

A very similar method was used in this paper for prime factorization, to apparently great success

- Scaling up prime factorization with self-organizing gates: A memcomputing approach by Tristan Sharp, Rishabh Khare, Erick Pederson, and Fabio Lorenzo Traversa

However, it's not clear to me exactly how they're designing the potentials. It seems like they're converting it to an integer linear program which is then converted to an SAT problem, and the clauses of the SAT representation are then turned into potentials. That would give the system as a whole and the memory in particular much higher dimensionality than what I implemented here. If it follows the papers I mentioned previously, then it also may treat the "rigidity" domain, when short-term memory indicates satisfaction, significantly differently than I did here. I suspect there's some simple, subtle modification that might work well. I tried hyperparameter tuning, but it didn't seem effective, but I wasn't totally thorough.

Limitations, variations, and future directions

There are lots of different ways to physicalize solving a logic program. The method I picked was particularly simple for how effective it is, but there are many alternatives. One can use simulated annealing methods to randomly jump around the potential while also descending, for example. Another topic that's seen a lot of interest recently is that of Ising machines. One can take a multinomial representation for the potentials described in this post and turn them into a 2nd-degree multinomial by introducing new variables as part of a process called "quadratization". A 2nd-degree multinomial can then be interpreted as the Hamiltonian of an Ising machine, and the ground state of such a machine would encode the solution to the problem originally encoded in the potentials. So if you ever heard about Ising machines and wondered how you're supposed to program one of those things, that's your answer.

In the previous papers I cited, particular emphasis was put on the disappativness of the system. That is, one would like to establish that the divergence of the vector is negative, ensuring that volumes tend to decrease in size over time. If we calculate the divergence of the system we would want to know the derivative with respect to of .

All of the atomic potentials I considered have a constant derivative with respect to any particular , meaning the divergence would be 0. In the original SAT implementation, the potential is defined in two different ways depending on whether the short-term memory is satisfied. If it isn't satisfied, then the gradient function is defined in terms of only the other variables, so the divergence is 0. However, a different potential is used when the short-term memory is satisfied. Instead, the gradient pushes a value toward whatever value it needs to be to continue satisfying the clause it appears in so long as it can take responsibility for said satisfaction. This is done by minimizing the difference between the variable and the constant value it needs to take. This is an essentially linear and negative dependence on the variable, creating a net negative divergence. This is easy for disjunctive constraints as a single variable can be pushed to a specific value to make the whole clause satisfied. I'm not sure what the analog of this would be in the more general cases considered here. Perhaps one must design a potential, or family of potentials, that have the proper minima while having negative . It's not hard to do this with the multilinear functions. Assuming the domain is , we can modify our multilinear function to be

However, implementing this change (as well as quite a few variants) didn't seem to help, so there's clearly more I'm missing.

One reason the SAT-based formulation of prime factorization might work better is due to how rigidity is handled. In the equations, the force keeping a variable unchanged is only applied if it's responsible for causing the clause to be satisfied. In the case of SAT, all constraints are just iterated disjunction, so whichever variable has the highest value automatically gets sole blame. Another way of saying it is that, so long as a clause remains satisfied, the variables not affecting this can move freely. Multilinear constraints already do this but with some limitations. In an xor constraint, for example, to jump between the two satisfying configurations a force must be built up to overcome the intermediate potential along the diagonal of the square. In the case of disjunction, all the satisfying instances are connected by a face of 0 potential, meaning no force has to be built up to move between them. Better multilinear potentials may have the additional property that all satisfying instances are connected by some face, implying additional variables implementing something like a Tseytin-transformed version of our starting potential.

For modeling more structured data types, one can look toward linear logic. Sweedler semantics (see Logic and linear algebra: an introduction) provides a way to interpret linear logic formulas as vector spaces. This allows one to turn structured combinatorial objects, described as linear types, into vector spaces, and specific data and algorithms arise as proofs turned into vectors. This idea was used to synthesize programs, with limited success, in this paper. Perhaps these modeling methods can be mixed with the solving methods mentioned here to make something more successful.

Unfortunately, a lot of the theory underlying the particular method I highlighted here relies on some high-level physics concepts that I'm not very familiar with. Mainly something called the "supersymmetric theory of stochastics". 🤷

If you're interested in running the code in a notebook, you can find the full code for this post at this gist. You can also find a somewhat messy SAT solver based on these methods that I wrote in Rust here.

Conclusion

To sum up, we explored solving logical problems by transforming them into ODEs. In each case, we translated the problem into a potential that reached a minimum at the solutions to our problem. By following the gradient, with some additional modifications to bypass local minima, we were able to solve several problems and saw that the interface for this can be compared to logic programming.